In a previous post, we discussed some of the tax implications and opportunities for business taxpayers as a result of the CARES Act, including allowance of net operating loss (NOL) carrybacks. Although CARES Act provisions are intended to provide taxpayers with much-needed short-term liquidity, the interplay of various rules can lead to unexpected results for multinational corporations. The NOL rule changes, as discussed below, will have significant tax implications for taxpayers in the U.S. international context.

Recent NOL Rule Changes

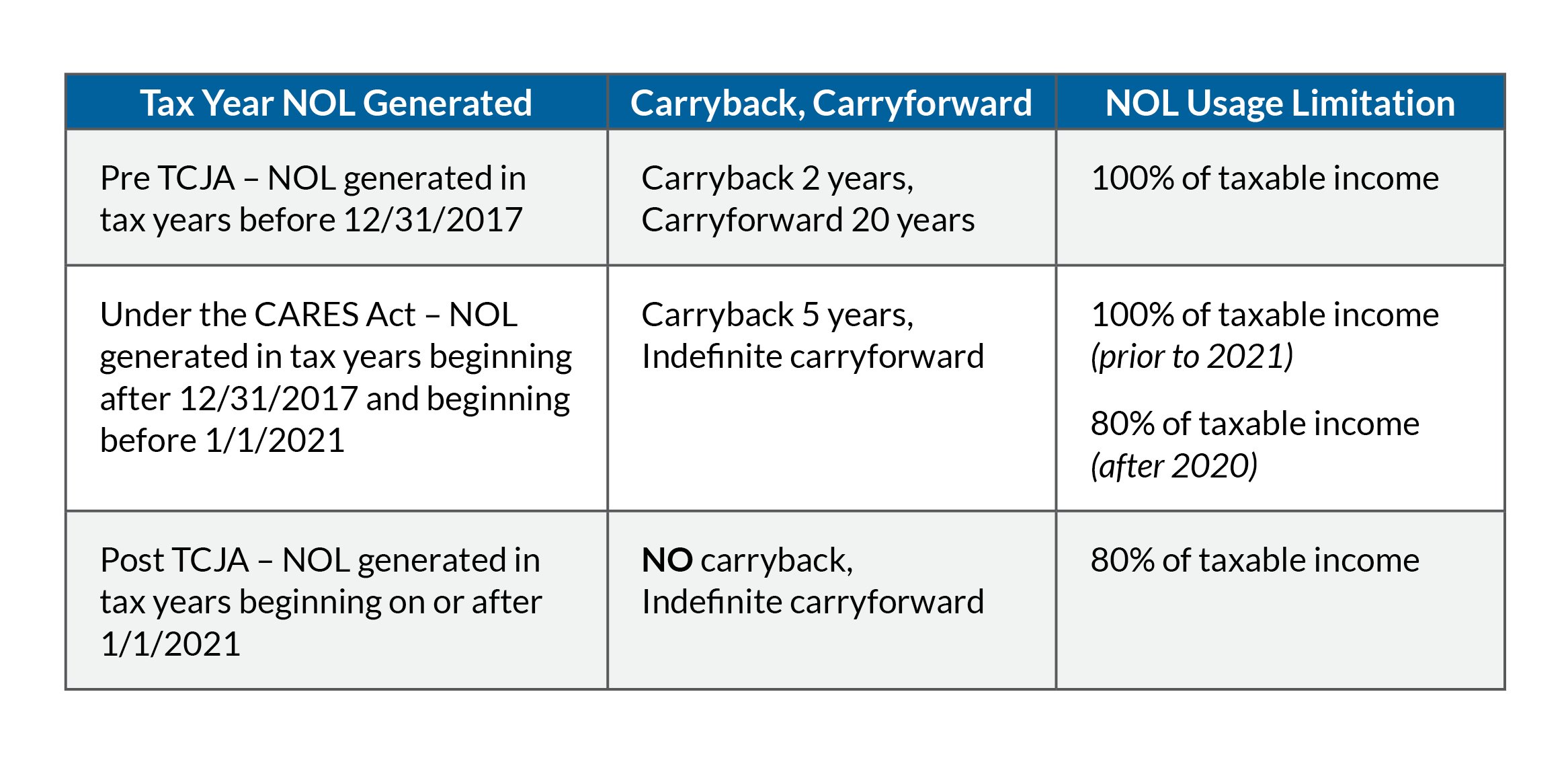

Under the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), NOLs arising in tax years beginning after December 31, 2017, could only offset 80 percent of taxable income in future years. Carryback of these NOLs was no longer permitted, but losses could be carried forward indefinitely.

The CARES Act permits a five-year carryback of NOLs generated in tax years beginning in 2018, 2019 and 2020. Additionally, the 80 percent limitation is temporarily suspended, but is reinstated for tax years beginning after 2020.

Different rules apply to NOLs based on the year in which they are generated, as summarized below:

Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income and Foreign-Derived Intangible Income

Global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) and foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) are categories of income, as enacted as part of the TCJA. In simplified terms, GILTI is income earned by a controlled foreign corporation above a 10 percent expected return on its depreciable tangible property. The GILTI regime is meant as a minimum tax on foreign income, with a 50 percent deduction allowed to U.S. corporations against GILTI meant to achieve a 10.5 percent effective rate of tax, as compared to the 21 percent statutory rate. Foreign tax credits (subject to a 20 percent “haircut”) are also allowed against the related tax, greatly reducing the tax liability for profitable U.S. corporations.

The foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) rules provide for a deduction against the income from the export of sales and services by a U.S. corporation. The FDII deduction is meant to reduce the effective tax rate on this export income to as low as 13.125 percent (through 2025) for profits above a 10 percent return on depreciable tangible property

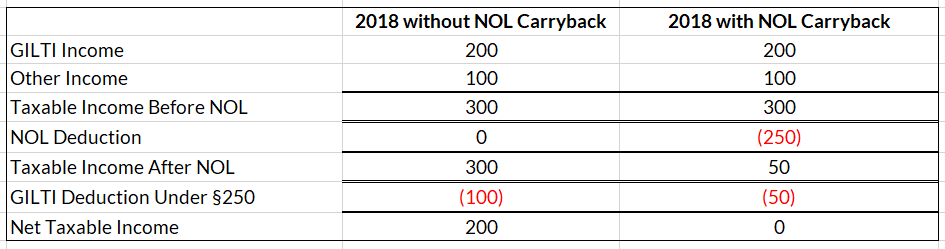

The 50 percent deduction against GILTI and 37.5 percent FDII deduction (both under Section 250) are limited to the taxpayer’s taxable income after the NOL deduction. Accordingly, carrying back NOLs may not provide the expected benefit if a taxpayer’s Section 250 deduction is then limited by taxable income. Even worse, the forgone Section 250 deductions cannot be carried forward.

In the example below, with the $250 NOL carried back to 2018, the GILTI deduction is capped at $50. The forgone Section 250 deduction of $50 is permanently lost.

It is also important to note that no carryover or carryback is allowed with respect to excess foreign tax credits (FTC) in the GILTI category. Thus, NOL carrybacks may also result in a permanent loss of FTC benefit.

Section 965 Transition Tax

Section 965 levied a transition tax on U.S. shareholders’ pro rata share of certain foreign corporations’ untaxed foreign earnings accumulated after 1986 and before December 31, 2017. The effective Section 965 tax rates imposed on U.S. corporations were 15.5 percent on earnings to the extent of the specified foreign corporation’s cash position and eight percent on the remaining non-cash portion. C corporations had the ability to claim a limited FTC against the transition tax. Further, taxpayers were allowed to make an election under Section 965(h) to pay the transition tax over an eight-year period with no interest.

The CARES Act provides specific rules for NOL carrybacks to a Section 965 inclusion year (2017 or 2018). First, a taxpayer is allowed an election to skip over 965 inclusion years entirely when carrying back losses. Taxpayers who choose to carry back NOLs to Section 965 inclusion years are deemed to have made a Section 965(n) election and are not allowed to offset any Section 965 income with NOL carryback deductions. In other words, taxpayers can only use the NOL carryback to offset its non-965 income and may not obtain a reduction or refund of the Section 965 tax. If the taxpayer made an election to pay the Section 965 tax liability in installments, the amount calculated as a refund due to NOL carryback against non-965 income will first be applied to subsequent transition tax installment obligations, before being available for a refund. Therefore, the election to skip Section 965 inclusion years may be attractive to taxpayers whose primary goal is to maximize a current cash refund.

Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax

The base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) is a minimum tax on large multinationals. BEAT applies only to corporations with average annual gross receipts of at least $500 million for the prior three years, with a base erosion percentage above three percent. BEAT is applied if a taxpayer’s modified taxable income times the applicable tax rate (five percent for 2018, 10 percent for 2019-2015 and 12.5 percent thereafter) exceeds the taxpayer’s regular tax liability. An NOL deduction reduces a taxpayer’s regular tax liability, which could create or increase a BEAT liability that would not otherwise apply.

For multinational taxpayers, the determination of potential benefit from NOL rule changes under the CARES Act requires a thorough analysis of the interaction with international tax provisions, such as the transition tax, GILTI, FDII, Section 250 deduction and BEAT. Careful tax planning is critical to ensure that taxpayers maximize the utilization of NOL carryback or carryforward claims.

Visit our Coronavirus Resource Center for the latest guidance and insights. Contact your RKL advisor with any questions and analysis and filing needs.